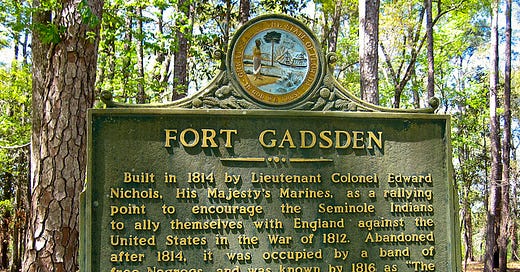

Sometime in the late 70s or early 80s, my family took a trip up to the Florida panhandle. On a cold and cloudy day, down a dirt road northwest of Tate’s Hell (yes that’s a real place), we arrived at Fort Gadsden State Park. I was young, but I paid attention to historical places and all that I gained from the trip was the knowledge that there had been a fort in the middle of the woods named after James Gadsden, the grandson of the designer of the “Don’t Tread on Me” flag. My dad was a history nerd like me, and I suspect there was a deeper reason for him driving us all out there, but he didn’t share that with me. The name stuck with me for some reason, but I never gave it thought until I was researching for my cookbook and came across the story of “Negro Fort.”

We all know that the winners get to write the history. Because of that, the stories of Negro Fort skew in multiple directions. I’ve had to decide for myself what is the most plausible and realistic telling of the story. I’m going to point out the multitude of conflicting information where it exists, you may decide for yourself which pieces you want to believe.

We all know a little about the War of 1812. The British wanted to take back the US, Francis Scott Key, the Whitehouse burned, Andrew Jackson killed a bunch of Brits in New Orleans after the war was officially over. There were many moving pieces that don’t get much air time, though. It was hard to tell which European countries were friends on any given day, but Spain and England were friends at the time, and Spain lent them limited support via Florida. At the same time, Tecumseh was working to unite Native nations west of the Appalachians to fight against US intrusion and control of their territories. Story short, Tecumseh saw what the future held if Native people failed to unite. Opposing views of his message (among other things) caused a rift in the Creek nation that broke down into civil war. (I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that Creek was a lazy white dude term for Muscogee speaking people who happened to be living alongside - wait for it - creeks in what are now Georgia, Alabama, and Tennesee.) The result was Creek on Creek fighting, Red Stick Creeks siding with the Brits, and some White Stick Creeks siding with the US.

The Creek civil war ended badly for the Red Sticks, many of whom took up residence in Spanish Florida. It was their land to begin with but had the added advantage of the US not trying to kill them. They were absorbed into the confederated group known as the Seminole who had started emerging about 60 years prior.

At the same time, Florida had been a haven for free Black people for over 100 years, due to Spain’s RELATIVELY liberal slavery laws. Originating with Gullah Geechee people in coastal Carolinas who followed the Low Country down, one could escape enslavement, slide across an imaginary line, and live freely with the knowledge that one’s children would also be born free.

During the bigger war at hand, the British constructed a fort on a bluff on the Apalachicola River from which they could control the river’s access to and from the Gulf and a base of attack across the border into Georgia, about 60 miles away. The garrison consisted of regular British troops as well as colonial marines - Black soldiers who were oddly inclined to fight against the Americans to ensure that their quality of life (not being enslaved) remained the way it was. At the end of the war, commanding officer Edward Nicolls and his regular troops abandoned the fort, leaving it fully stocked in the hands of the colonial marines and a group of Seminoles, Creeks, and Choctaws who had aided the British efforts.

What followed was a short but peaceful life at the fort. More free Black people migrated to the fort from across Florida, the settlement and farms around it expanding several miles up and downriver. Rumors of this idyllic place where hundreds of Black and Native people could live freely spread throughout the South and served as the impetus for enslaved people as far away as Tennesee to escape their servitude.

Of course, this could not be abided by enslavers to the north. An autonomous Black society offended their sensibilities, and the prospect of freedom seekers threatened the institution of enslavement, upon which their bank accounts were built. Fictionalizing cross-border “Indian” raids from the fort to manifest a physical rather than merely existential threat, they demanded help from Washington. Always willing to help the landed gentry retain their wealth with military support, the federal government answered their demands in the form of Andrew Jackson.

Already knowing the response, Jackson wrote to the Spanish governor, telling him to handle the situation or he and the US military would. From his headquarters in New Orleans, Jackson ordered the construction of Fort Scott on the Georgia border where the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers meet to become the Apalachicola. US ships started navigating the river, claiming that the only way to get materials and supplies to Ft Scott efficiently would be up the Appalachicola, passing repeatedly in front of the fort and settlement in a not at all intimidating manner.

What happened next was likely as imaginary as the “Indian” raids that the Georgia plantation owners whipped up, but set the stage for tragedy. Stopping to gather water, the residents of Negro Fort supposedly attacked the crew of one of the supply ships. Dubbed “The Watering Party Massacre”, three of the party were reported killed and one captured and burned alive. Other accounts tell of ships fired upon as they passed the fort. Still others speak of the fort leader, Garçon (sometimes spelled Garson), a freed enslaved person, declaring that any US ship attempting to pass the settlement would be destroyed. It’s safe to say that there was some type of hostile interaction. It’s also safe to say that the Americans probably provoked it.

Questions are raised here:

Why would a US Naval vessel need to stop for water just 20 miles upriver from the Gulf? It seems highly suspect that they would need water just one day after entering the mouth of the river.

Why would the fort fire on gunships when the story that follows clearly states a lack of a vital component to be successful in this?

With reason in hand, whatever the verity of that reason may be, the US Army made their move to squash this stronghold of not-white assholes who were aggressively trying to live their lives in peace. Under General Edmund P. Gaines, Colonel Duncan Clinch led a party of gunboats from the south and infantry and Native fighters from Ft Scott to destroy this offense to white supremacist ideology. On July 27, 1816, they arrived and in a Han Solo/Greedo exchange, some claim that Garçon fired on the gunboats. It’s agreed that the former marines and Natives manning the defenses had no artillery experience, and if they did fire first, they failed miserably. If it even occurred. To my point above; how does one have no experience yet regularly fire on passing ships?

The Americans didn’t have the same problem. Some versions claim a lucky shot, others claim that one of the gunboats fired a super-heated cannonball, either way, the first shot landed directly in the powder magazine of the fort, causing a massive explosion that was heard 100 miles away in Pensacola. Depending on the source, between 270 and 330 men, women, and children, Black and Native, were killed instantly. Some report all survivors dying shortly after of their wounds, others say those that lived left to form other settlements in Florida and the Bahamas.

Among the survivors were Garçon, an unnamed Choctaw chief, and an unnamed formerly enslaved person, all of whom were captured. Garçon and the formerly enslaved person were immediately executed by US troops for their part in the questionable Watering Party Massacre, while the Choctaw was handed over to the Creeks assisting Clinch and summarily scalped before being killed. There were zero casualties on the US side. Unlike the four people who may or may not have been killed while gathering water, historical records rarely refer to this event as a massacre. It’s only a massacre when white people do the dying.

In the aftermath, retaliation for this attack led to the onset of the First Seminole War, in which Jackson again invaded Spanish Florida with an agenda of subjugating non-whites. Seeing the location on the bluff as advantageous to his purposes, he ordered the fort rebuilt by Lt. James Gadsden, of the US Army Corps of Engineers. The name remains today. That’s what history tells us is important - a white dude built a fort here.

It should be noted that a large supply of English weapons survived the explosion somehow. Hundreds of pistols, muskets, cutlasses, powder, and balls were distributed to the Creeks who aided Clinch on the raid. As the weapons were still in their crates, maybe the folks at Negro Fort weren’t launching raids into Georgia or killing watering parties after all. But none of that matters in the history books.

Duncan Clinch went on to fame in other parts of Florida; like inadvertently causing the Dade Massacre (that launched the Second Seminole War) and bungling the Battle of Withlacoochee shortly after. Jackson, as we know, went on to kill many more Native people and be memorialized on US currency for it. Gadsden went on to be the ambassador to Mexico and negotiated the purchase of southern Arizona and New Mexico. The park transferred to the US Forest Service, where it is now known as the Fort Gadsden/Prospect Bluff Historic Site. No mention of Negro Fort.

Have I mentioned white supremacy? I’ll say it again because it is at the heart of all things Florida. It was the driving force for the US acquiring Florida as a territory and continued to be the guiding doctrine for the next century. A doctrine that included four wars on Florida soil to kill or subjugate those who weren’t white and European. It’s simple, Florida was born into blood.